childhood asthma risks

Exposure to certain pet and pest allergens in infancy may lower a child’s risk of developing asthma by age 7, according to a new study conducted by Washington University School of Medicine and other universities. The study looks at inner city children at high risk of developing asthma. Along with St. Louis, Baltimore, Boston and New York also were included. Researchers theorize that certain allergens carry bacteria that protect against respiratory problems, explaining the counterintuitive findings. The study also found that the mental health of the mother significantly impacts the child’s asthma risk. Greater risk is associated with mothers experiencing higher levels of depression and stress. “We may not need to worry about making sure the household environment is maximally clean—in fact, it’s possible that could be counterproductive,” says co-author Dr. Leonard R. Bacharier, a Washington University asthma specialist. “But helping women manage the challenges of mental health may make a difference.” The research is published in The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

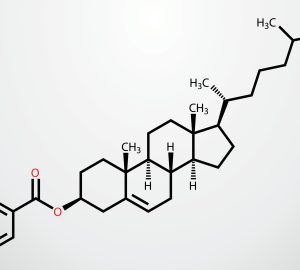

t-cell immunotherapy

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved a new, personalized cell therapy that supercharges the patient’s immune system to find and kill cancer cells. The therapy, axibabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta), is supported by the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (LLS) and is the second therapy for a new method of treatment known as CAR (chimeric antigen receptor) T-cell immunotherapy. It uses genetic engineering to reprogram the patient’s immune T-cells to target cancer cells. LLS has invested more than $40 million in research and development for CAR therapy. It supported the clinical trial leading to the approval of Yescarta through its Therapy Acceleration Program, which partners with biotechnology companies to accelerate the development of promising treatments. Yescarta is for patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, the most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It offers a 60 percent, five-year overall survival rate, and 25,000 people in the U.S. are expected to be diagnosed with the condition in 2017. In the trial, 51 percent of patients treated had a complete response with no detectable cancer remaining.

targeting dux4

Fascioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) is an inherited type of the condition that affects more than 800,000 people worldwide, and there is currently no cure. Scientists have learned that the DUX4 gene is responsible for FSHD. Dr. Francis M. Sverdrup, a research fellow in the Saint Louis University department of biochemistry and molecular biology, has used this discovery to identify new drug targets to slow or halt the progression of the disease. Sverdrup and a research team identified two classes of drugs that turn off DUX4: BET inhibitors and beta agonists. The former already is being studied in clinical trials for cancer, and the latter is widely used to treat asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. “It’s encouraging that our first two screens yielded molecules that turn off DUX4, and this provides hope that additional candidates can be identified in larger screens,” Sverdrup says. He is working with Ultragenyx Pharmaceuticals to optimize potential treatment specifically for FSHD. Sverdrup’s paper on the subject is published in the journal Skeletal Muscle.