More than 6 million Americans are living with Alzheimer’s disease, and by 2050, that number is projected to reach 12.7 million, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. There is currently no cure for the disease, but there is a light at the end of the tunnel. For the first time, the United States Food and Drug Administration has approved a drug for Alzheimer’s treatment: lecanemab, sold under the brand name Leqembi.

What is Leqembi?

The drug is an antibody intravenous (IV) infusion therapy that is given every two weeks. It is important to note that Leqembi is not a cure for Alzheimer’s disease, but it is the first traditionally approved treatment that has been shown to change the course of the disease for patients in its early stages. In clinical trials, it has been shown to slow the progression of the disease. At Washington University, a study showed that the drug slowed decline in memory and cognition by about 30% over the course of an 18-month treatment. There is no evidence that it can restore or reverse lost memories or cognitive function that has already occurred.

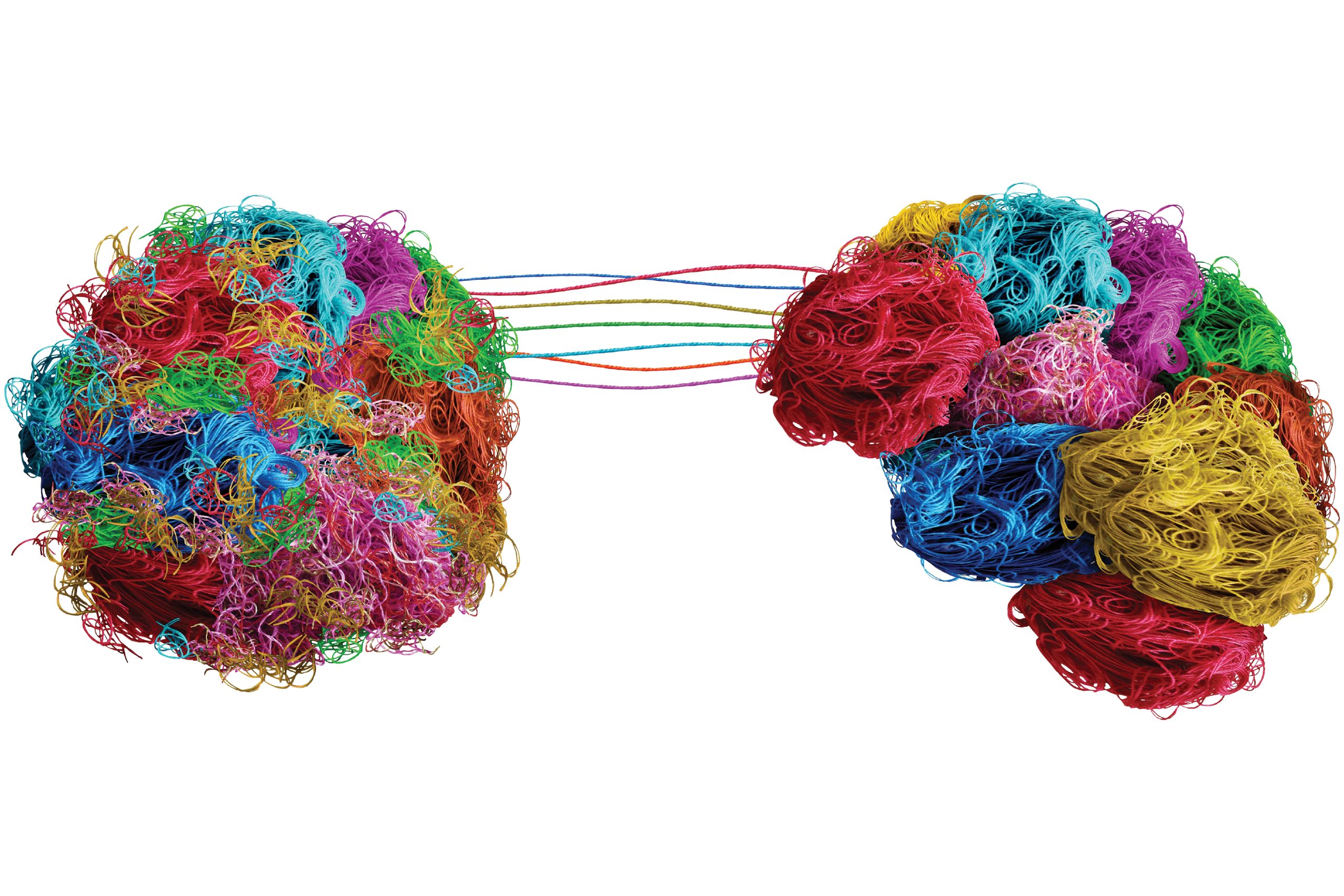

How does it work?

One of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s is beta proteins that aggregate in the brain, creating buildup known as amyloid plaques. These plaques are believed to interfere with memory and cognition. Studies have shown that Leqembi removes amyloid plaques, slowing the progression of the disease.

Could Leqembi or another similar drug help prevent Alzheimer’s?

According to the Washington University School of Medicine, anti-amyloid drugs like Leqembi could lead to better preventative measures. This is because amyloid plaques are one of the first abnormalities in the brain that leads to the development of Alzheimer’s. In theory, an anti-amyloid therapy given very early, such as before the appearance of any memory problems, may be the most effective way to stop the progression of the disease and cognitive decline. In an ideal scenario, early enough intervention would be able to prevent the disease from developing entirely. While there is currently no evidence that Leqembi can do this, future research is moving toward that goal. The AHEAD study is currently evaluating whether Leqembi is effective in people who are at risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease but do not yet have symptoms.

Who is eligible to take Leqembi?

Leqembi has been studied in patients living with mild Alzheimer’s dementia who showed evidence of a buildup of beta-amyloid plaques in the brain. The FDA has determined that the drug is appropriate for people with early Alzheimer’s with confirmation of elevated beta-amyloid. According to Washington University School of Medicine, that accounts for around 15% to 20% of Alzheimer’s patients. Leqembi has not been tested on people with more advanced stages of the disease or those without clinical symptoms.

Are there any known side effects?

Leqembi was generally found to be safe, but in around 25% of people, it did have some potentially serious side effects. According to the Washington University School of Medicine, some patients experienced microhemorrhages (areas in the brain with small amounts of bleeding) or swelling. In most cases, these side effects didn’t come with symptoms, and they mostly resolved on their own. However, some patients experienced headaches, confusion and stroke-like symptoms.

How much does it cost?

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, the manufacturers of Leqembi announced they are setting the price of the drug at $26,500 a year. Medicare may cover up to 80% of that cost, but that is not the only expense associated with the drug. Determining eligibility will likely require costly PET imaging and MRI scans, which may not be covered.

Was there local research that helped make the drug possible?

The Charles F. And Joanne Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Washington University was involved in the trials that evaluated Leqembi. The center also has conducted a lot of other research to make Alzheimer’s treatments possible. Local researchers developed methods to determine if a person with symptoms has Alzheimer’s, such as amyloid PET imaging scans, blood tests and spinal fluid tests. Washington University also has led the DIAN (Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network) study, which looks at people with inherited gene mutations that indicate Alzheimer’s disease will develop. The goal is to establish reliable biomarkers that track the disease’s progression, and it also has evaluated the effectiveness of other Alzheimer’s drugs in preventing or slowing its onset.

Sources: Washington University School of Medicine, Alzheimer’s Association