the metro | The accompanying photo of a monarch butterfly is from about 10 years ago, when the only discussion about the beautiful insect was via exhortations from environmental groups to plant butterfly gardens. I was living in a city flat at the time, and my landlady had a variety of flowering bushes on the lot that attracted all manner of flying insects, from bees to butterflies. I also have a photo of a bumblebee gorging itself one summer day on a solitary sunflower, which had ‘volunteered’ after sprouting and growing taller than the birdfeeder, probably because some squirrel had kicked out a seed that spring. Butterflies flitted about all summer, and monarchs were plentiful. One fall day we watched in awe from the front balcony as an immense, bright-orange mass overhead flew south on its migration to the Sierra Madre Mountains in Mexico to hibernate. Monarchs are on the move even as we speak. Alas, there aren’t as many of them. I don’t remember seeing one this year, and they’re hard to miss, what with their striking Halloween colors of orange and black, complemented by white spots on their fuzzy black bodies and the edges of their wings. Well, the species is now endangered! But how? Habitat destruction and, what else, extreme weather from climate change. Now, we can’t just leave their protection to the dedicated conservationists at Missouri Botanical Garden and its Sophia M. Sachs Butterfly House in Chesterfield, although some folks may just shrug and hum, “Another One Bites the Dust.” Hum away. It’s like whistling in the dark. A few millennia from now, when paleontologists from some advanced civilization dust off the fossilized bones of homo sapiens, they’ll complain about the same obnoxious pests as we had millions of years before we ourselves went extinct: Why can’t we ever get rid of mosquitoes, cockroaches or rats? Or sweetgum trees?

creve coeur

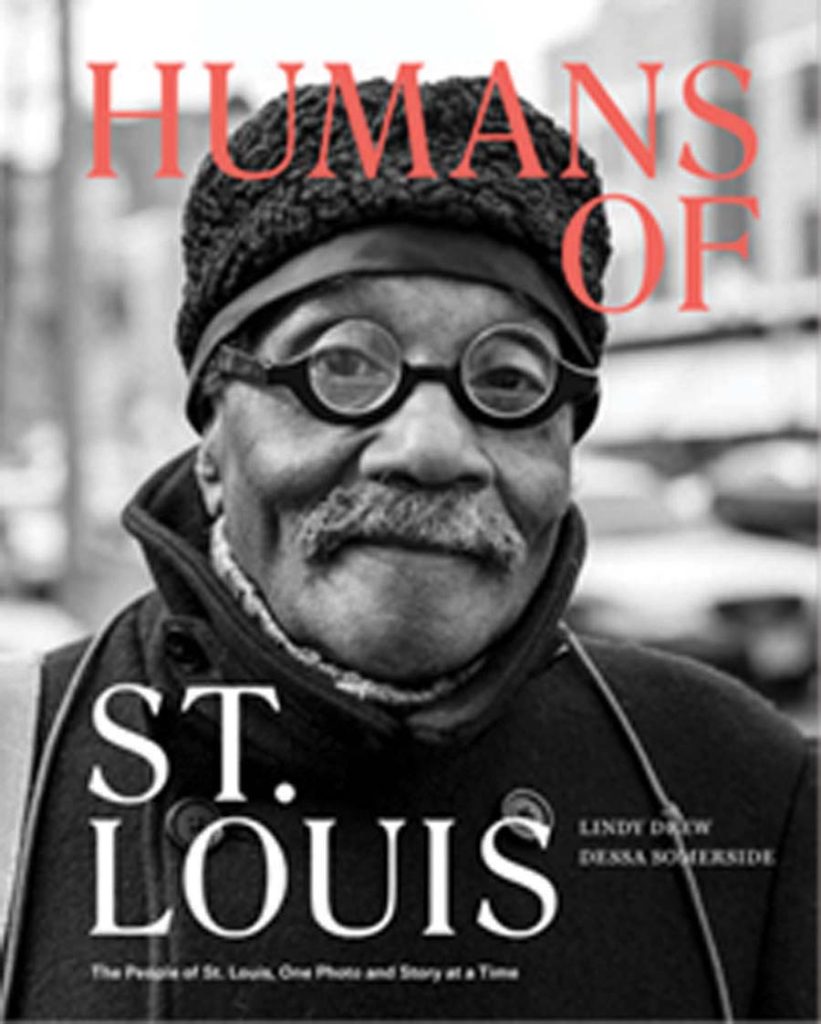

Are you familiar with the online juggernaut “Humans of New York,” a social-media sensation developed by photographer Brandon Stanton? It popped up on my Instagram feed several years ago, and I’ve been following it ever since, along with 3.8 million others—and 15 million on Facebook! Since 2010, Stanton has been doing compelling street interviews that touch your heart and often spur donations to the people he covers, whether refugees, the down and out, young people with a dream … you name it. He’s produced two enthralling, hard-to-put-down books. People worldwide have adapted the concept to help others in their communities, among them our town’s own Lindy Drew, whose book Humans of St. Louis is to be spotlighted in a Nov. 12 panel of ‘Missouri’s Own’—Drew and three other authors—at the J’s Performing Arts Center, 2 Millstone Campus Drive. Just look at her book’s cover. Don’t you want to know that man’s story? Drew started out by knocking on doors to see who might be willing and able to help out, then her crew fanned out to find a broad spectrum of our neighbors. The book would not have been possible without the support of St. Louis Community Foundation, says Drew. Online, HOSTL gives more than 130,000 social media followers an intimate look into the lives and struggles of the people here, one photo and story at a time. Highlights: economic growth, philanthropy, small businesses. Stories also address issues such as racial equity, gender and LGBTQ rights, community, family, youth, aging, health, disease, education, homelessness, poverty and cultural awareness. Drew’s project is the second most-popular ‘Humans of’ after New York’s. The local-authors panel session is smack-dab in the middle of the St. Louis Jewish Book Festival, which runs Nov. 5-19. Visit jccstl.com/festival-events-schedule.

u. city

We order more pizza delivered from Papa John’s than our primary-care physician would like. It’s not too healthy, of course. She wants us to choose foods from the Mediterranean diet, which is probably salad without dressing—lettuce, lettuce, more lettuce and cauliflower. I’m not really sure what the diet encompasses, actually, but at every appointment she gives me the same four pages that I glance at, say, “yuck,” then call Papa. My taste buds tell me I need my fat, salt and sugar. I don’t know when Papa changed his ordering process, but now, it’s offshore. Papa is not Amelia or Josh, some harried teenage restaurant employee trying to do three jobs at once, but a very cordial person taking calls from the Philippines, where it’s very early Tuesday morning if I’m ordering at 7 p.m. Monday from U. City. They always get the order right. I think the delivery person has left out the two-liter soda once or twice, but I can’t really blame that on someone halfway around the world, right? They always ask you whether you want to add a tip. (More on that in the next few lines.) At the end of every call, they switch you over to an automated operator that asks you to rate the ordering experience. It’s always fine. It’s the completed delivery I’m concerned about, and I can’t decide whether to tip 20%, my usual amount since the pandemic, before the delivery is complete. And by who? Recent deliveries have been made by someone from DoorDash, not the pizzeria. My, my. Does it really have to be this complicated?

notable neighbors

notable neighbors

kirkwood

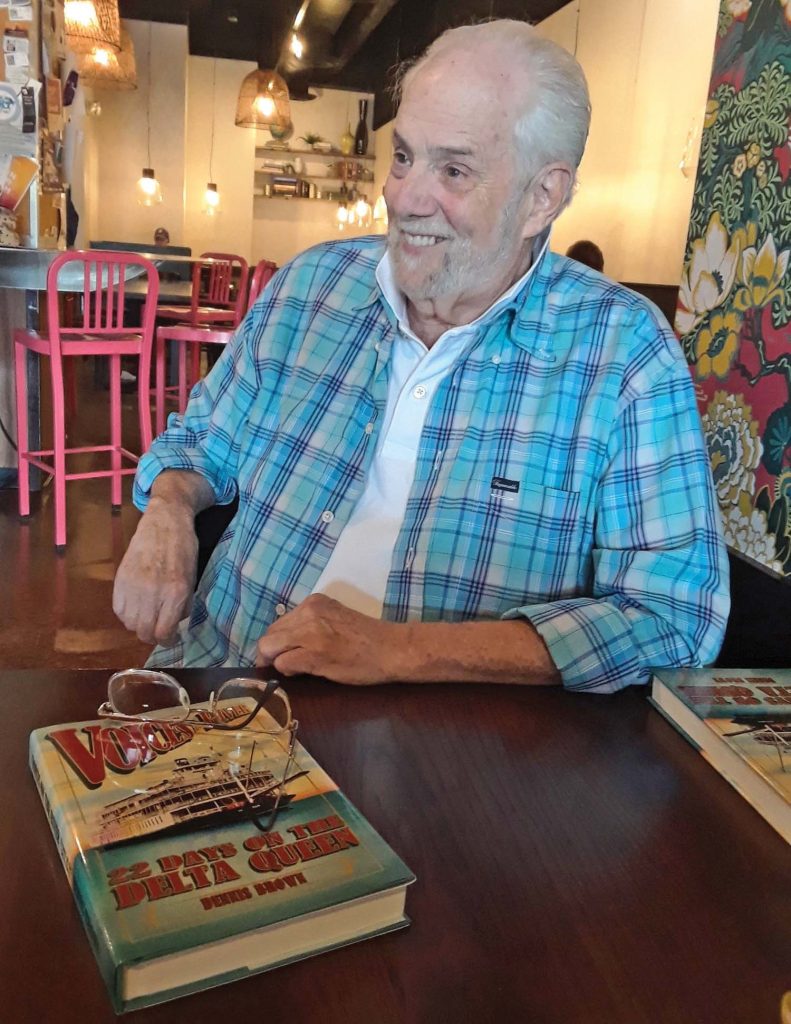

When you sit down with author Dennis Brown of Kirkwood, you can be forgiven if you can’t shake the lyrics to a 1960s pop hit out of your head: “Big wheel keep on turnin’ / Proud Mary keep on burnin’ / Rollin’, rollin’, rollin’ on the river.” Brown’s latest labor of love is Voices on the River: 22 Days on the Delta Queen. Along with the Mississippi Queen and American Queen, the ‘DQ’ was one of several vintage paddle-wheelers that plied the Mississippi and other major rivers in the heartland for decades, and Brown started many years of cruising in 1986. Brown may as well have captained the stern-wheeler himself, what with his more than 200 overnight stays on the DQ over the years. And, why not? Imagine accommodations on a cruise ship as luxurious as the Queen Mary, with accoutrements from early-20th-century New Orleans. She was 285 feet from stem to massive paddle-wheel—much more grand than the replicas that take tourists for short excursions below the Gateway Arch. Built in the 1920s to ply the Sacramento River out of San Francisco, in the late 1940s she relocated, from the west coast via the Panama Canal to enter regular passenger service in the Midwest, cruising the Ohio, Mississippi, Tennessee and Cumberland rivers between New Orleans, Cincinnati, St. Paul, Paducah, Nashville, Chattanooga and ports in between, St. Louis among them. After going out of service and being converted into a Chattanooga boutique hotel, city fathers decreed she was an obstruction. The grand old steamboat has been docked at Houma, Louisiana, since the mid-2010s. “The Delta Queen has been awaiting its fate for several years now,” says Brown, expressing a fervent wish that she doesn’t come to an ignominious end, as did the Mississippi Queen, which after its sale was stripped and reduced to a dock somewhere. Brown asserts the previous owners are still living with guilt that the fine vessel was destroyed. Nothing lasts forever, of course, but Brown has captured his memories and those of many other passengers and her longtime pilot, Capt. Fred Way, in a volume that’s equal parts historical narrative, travelogue, reminiscence and tribute. He speaks fondly of the halcyon days when the Goldenrod and Admiral both lent our riverfront a more sophisticated air, if you will. If before the turn of the 19th century, the enemy of the railroad was the steamboat, an enemy of tight, lively writing is, simply, superfluous verbiage. Voices is just a fun read. “I cut 30,000 words out of this,” Brown says. Otherwise, he adds with a smile, “it could have been the most pretentious book ever written.” (Brown must be familiar with that book professors assign English students that advises writers to hunt down the adjectives they’re thinking of using and kill them instead.) Riverboating will continue as long as the rivers flow, but never with the same elegance as in the days of the three Queens aboard which Brown has been fortunate to cruise, which he speaks and writes about with reverence and humor. And this is from a man who’s worked in TV and film in NYC and L.A. and taught a film-appreciation course at Webster U. for 15 years. He chuckles, “That’s the most rewarding thing I’ve ever done, other than cruising on a steamboat.”