The 10 warning signs of Alzheimer’s are displayed prominently on the Alzheimer’s Association website. They are clear. They are descriptive. They plead with people to seek a doctor if any sign is recognized in a loved one. “Early and appropriate treatment means they may be able to stay home an extra two years before moving into a nursing home, if that is their choice,” says Stephanie Rohlfs-Young, vice president of programs for the St. Louis chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association.

The Alzheimer’s Association wants to help, but the challenge is that half the people who have the disease do not get a diagnosis, Rohlfs-Young says. Primary care physicians may tell a person they have dementia, but the patients don’t always find out what type. Dementia is a broad term that describes cognitive loss, and Alzheimer’s is one type of dementia. “Treatments vary depending on the type of dementia,” she says.

The Alzheimer’s Association continues to grow its programs designed for those in the early stages of the disease. Its classes and support groups center around education and living with the symptoms. “We try to make it clear you still have a lot of life ahead of you,” Rohlfs-Young says. “You just need to make modest adjustments. A diagnosis does not mean you have to shift what you do radically.”

The Alzheimer’s Association continues to grow its programs designed for those in the early stages of the disease. Its classes and support groups center around education and living with the symptoms. “We try to make it clear you still have a lot of life ahead of you,” Rohlfs-Young says. “You just need to make modest adjustments. A diagnosis does not mean you have to shift what you do radically.”

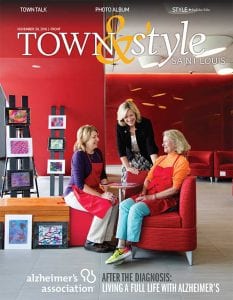

With an early diagnosis, the association is able to enhance life for those diagnosed and their caregivers through support groups and education. The local chapter has partnered with other organizations to provide more activities, like an art therapy program at Maryville University called ‘Opening Minds Through Art.’ “They do a little bit of everything from mixed media to collages and acrylic painting,” Rohlfs-Young says. “It’s fascinating to see people with no art background tap into a creative side they didn’t even know they had.”

Another Alzheimer’s Association program is called Meet Up, and it offers a platform for people to get together about every three weeks to participate in a day trip, like visiting a museum. Let’s Talk also is offered every other Saturday to connect people via phone to someone else dealing with similar symptoms and troubles. “Alzheimer’s is very isolating for families,” Rohlfs-Young says. “People’s worlds get smaller and smaller. In my own family, my grandmother took part in the Let’s Talk program when she was diagnosed. She lived in a small, rural town and knew no one who could relate to her. It helped a lot when she started talking to her peer in the program because they could understand and relate to each other.”

The programs are intended for those still in the early stages of Alzheimer’s who can maintain conversations and handle their own personal care. “Naturally as the disease progresses, they enjoy groups less,” Rohlfs-Young says. “It can be overwhelming and scary, and that is when families start opting out of the programs.”

Due to the nature of Alzheimer’s patients, class sizes are kept small, which limits those who can sign up. The association hopes expansion is on the horizon. “We need volunteers for the programs—anyone from educators to people who can run the support groups,” Rohlfs-Young says. “It takes so much help to keep these programs thriving.”

Pictured: Care partner Bonnie Enos, the Alzheimer’s Association’s vice president of programs Stephanie Rohlfs-Young and client Darryl Enos

The Alzheimer’s Association is the leading voluntary health organization in Alzheimer’s care, support and research. Pictured on the cover: Maryville University’s Ashlyn Cunningham, Alzheimer’s Association of St. Louis president Stacy Tew-Lovasz, and Rita Loeffler, who is living with Alzheimer’s, surrounded by projects form an art therapy class for those with early-onset Alzheimer’s. For more information on how to volunteer or get help for a loved one, call 800.272.3900 or visit alz.org.

Cover deisgn by Jon Fogel | Cover photo by Colin Miller of Strauss Peyton